Acedia: The Noonday Devil

By Sr Rose Rolling o.p.

Map of the Journey:

For the last two months of our Holy Preaching series, we have found ourselves in what Evagrius understood as the trio of vices pertaining to the ‘mid-point temptations’, the adolescence, of our spiritual life. We have explored two of these – sadness and anger – and now we come to the third temptation in this unholy trio, and the topic for tonight’s talk, which is acedia.

These thoughts of sadness, anger and acedia afflict us when we’ve managed to get a basic handle on our bodily impulses of gluttony, lust and greed. Now it’s our emotions which are the main target of evil influences – an alteration between the strong emotions of sadness and anger on one hand, undercut by a complete lack of interest, distaste or tiredness called acedia, on the other.

Definition:

So what is acedia?

In pre-Christian times, acedia was defined as ‘not burying one’s dead’. Burying the dead is one of the defining acts of being human, and one of the most obvious ways we accord dignity – or not – to other human beings. A failure to bury the dead was understood as impious, unpatriotic, uncivilised, a punishment and fundamentally ‘inhuman’. Ruben Rivas points out in his research that in ancient Greek philosophy, care for the dead was linked to “the search for one's own identity and the existential meaning of the human person”[1].

The origin of the English word acedia comes from the Greek akedia meaning a ‘lack of care’ for one’s own spiritual life and salvation. With Evagrius, a new meaning develops: it is no longer about the failure to bury the deceased but about a lack of care for one’s own spiritual life, a lack of care which puts us in jeopardy of spiritual death. Evagrius defines acedia as atonia meaning ‘relaxation of soul’ by which he means a basic lack of spiritual energy. The word also has connotations of indifference, despair, laziness, boredom, disgust and a stifling of the intellect whose function it is to contemplate God. Acedia is all of these and more; it is described as “the complex thought” precisely because of its layers of meaning.

Characteristics:

So that’s our basic definition. What then are the characteristics of acedia?

One of acedia’s features is its tenacity. Unlike the other thoughts, it is not a transitional evil, a short-term crisis, but an enduring trial. This is what makes it so dangerous and why Evagrius labels it most oppressive of all the evil thoughts. However, this also makes victory over it all the more glorious.

Two other characteristics of acedia are how it affects space and time.

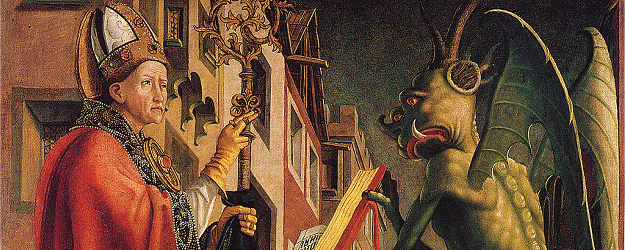

In relaation to the temporal dimension, Evagrius calls acedia the ‘noonday demon’. To put this into context, Evagrius wrote these thoughts primarily for the desert-dwellers, those Christians who had left everything for the sake of dedicating themselves wholly to Christ through a life of prayer, asceticism and solitude. In naming acedia the noonday demon, Evagrius is being very literal: the Egyptian sun would have been at its zenith between 10am – 2pm. The hot beating sun, accompanied by the strict fasting of one meagre meal per day in the later afternoon, and the weariness from night vigils would have laid a burden of temptation on the monk to give up altogether.

Aside from the literal meaning of its temporal dimension, we can apply its temporal challenges to the human life cycle or spiritual passage. Acedia is a particular temptation for those in the middle of the spiritual journey. This could either hit in the middle of our biological age (30s-50s) when all the responsibilities of life weigh heavily and the spiritual life is relegated to a back seat, or it could be the middle passage of our spiritual life, when the basic virtues have stabilised and the task is less of the aggressive spiritual combat of the early stages of rooting out serious sin, but now oriented towards holding onto the territory grace has won for us.

It is at this point that acedia starts to bite. The long years of steadiness and faithfulness to the spiritual life, or to a vocation, lose their attractiveness. Neither the enthusiasm and flush of youth nor the peaceful accomplishment of old age sustain us – instead we are just living in the slog of the mid-point, seemingly for many more years to come, without respite. Time seems endless and fruitless.

The time-warp is accompanied by a spatial dimension. The desert fathers committed themselves to staying in a specific place, something which is preserved by monastic communities today by their vow of stability. St Benedict, in his Rule, condemns the kind of monk he calls gyrovagues, who, he says, spend their entire lives drifting from region to region, staying as guests for three or four days in different monasteries. Always on the move, they never settle down, and are slaves to their own wills and gross appetites.

The temptation of the monk to ease his difficulty and dejection was to leave his cell, which in monastic literature is equated with the abandonment of the spiritual life. This ‘roaming around’ is understood as a cause and consequence of acedia, whereas continuity of physical place is seen as a sign and aid for continuity in the spiritual quest. In our society, it has never been easier to be roaming – cheap international travel, constant digital connection, and a smorgasbord of religions and spiritualities all make some form of ‘wandering off’ easier than ever.

However, although avoiding acedia is linked with geographical and interior stability, this must not be wrongly understood. Stability does not mean something which is fixed and unchanging; this can induce stagnation which in itself can be a cause and consequence of acedia. Rather, the Trappist monk Michael Casey uses the image of a surfboard rider to describe stability – it involves much energy to stand on the surfboard while the waves roll beneath; it requires maintaining a balance while everything around is moving. Stability properly lived should serve as a dynamic springboard to a changing world, not a static feature[2].

Relevance to the Christian Life Today:

So far, we have heard a lot about monks. But what about acedia’s relevance for all Christians, and for Christians in the contemporary world?

Acedia is probably the least known of the Eight Evil Thoughts, yet arguably it is the most pervasive vice afflicting the Church today in the Western world.

In previous talks on one of the Evil Thoughts, reference has been made to the insights of modern psychology in unpacking some of what is going on with the particular temptation. While psychological factors are present in acedia, I suggest that it is rather cultural factors which predominate in this struggle today.

To understand this, I will be referring to the cultural and historical factors outlined by Sr Sandra Schneiders, in her research on the obstacles facing those attempting to undertake a Catholic vocational choice today. Although Schneiders deals with a different question – in this case, the challenges to permanent vocational commitment in marriage or religious life today – the factors she cites are ones arguably caused by, or compounded by, the presence of acedia, and acedia ultimately boils down to the inability to persevere in spiritual things, which can include vocation. These factors are also ones with widespread consequences in the daily life of all Christians. Schneiders outlines them as follows:

The lack of permanence in anything – a job, a relationship etc. We are an extremely mobile world – geographically, but even more so intellectually with the advent of widespread access to digital communications. Not only do things change but they change extremely quickly: nothing stands still very long.

The second cultural factor is living in a consumerist society which provides and promotes a huge variety of continual choices, options and inevitably, upgrades. These range of choices either paralyse us or lead towards hopping from one thing to the next: both are contrary to growth. This plethora of choices has raised our expectations: we expect instant gratification in our endeavours. The failure to experience instant gratification sits underneath acedia and anger – the sadness and impatience connected with daily fidelity without tangible results.

The historical factor which compounds acedia is our longer life expectancy. The commitments we undertake today – to being practising Catholics, or to a vocation – are likely to last anywhere from fifty to eighty years. During these years, there will likely be significant shifts in geographical location, employment, relationships and our personalities. Maintaining our initial spiritual commitment in the midst of all these fluctuations is a major challenge but may also be a source of dynamism if we learn how to use them creatively.

Those are the cultural and historical trends that can feed acedia, but, meanwhile, acedia seems to have largely disappeared from Christian consciousness apart from in a few niche places like monasteries or manuals of spiritual theology. Where there is some mention of it, is too often equated with laziness understood as a failure to ‘work hard’, and applied to our worldly endeavours – our jobs, our household duties, our family obligations and finally, all the things on our spiritual ‘to-do’ list.

Defining acedia primarily in relation to ‘failing to work hard’ is a mistake, and worse, this misdiagnosis of the problem actually risks making the whole issue worse. If we think of acedia as mere laziness – I did not say all the private prayers I wanted to say, I did not answer all the work emails I intended – then we can try by our own effort to double down and add even more to our to do list, either in worldly things or spiritually.

The lack of awareness and/or misdiagnosis of acedia in Christian consciousness is a bad sign because it functions through quiet destruction: like mould, it thrives in dark places. We need to start exposing it to the light.

Manifestations:

So, having explored some general characteristics of acedia, let’s now move to its manifestations. Evagrius lists five main manifestations of acedia and we will look at each of these in turn.

- Interior instability.

Evagrius says that the “demon of acedia suggests to you ideas of leaving, the need to change your place and your way of life. He depicts this other life as your salvation and persuades you that if you do not leave, you are lost”.

This temptation is all the more pernicious because it often comes disguised under a good intention, for example, being flaky in our current commitments for the sake of rendering some other more pressing or useful service. For example, we may say to ourselves: well, I could go to Mass on Sunday or I could volunteer at the drop-in shelter. I choose the latter because it seems more helpful to others and God is present everywhere, so why does going to Church matter so much? This is the deception of acedie.

To combat interior instability, Evagrius recommends physical stability as this helps support stability of heart. For example, if we are tempted to give up prayer and to go out or do something else instead because it is difficult or dry, perhaps we should try to persevere just where we are, rather than go off and look for somewhere else.

Interior stability is more difficult now because of the limitless distractions at our fingertips available through digital communications – the whole world is only one click away through our phone or the internet even if we have not literally left the building. Being disciplined in avoiding an attitude of ‘roaming around’ whether physically or digitally can help us overcome acedia and strengthen us against the interior instability.

- An exaggerated concern for one’s health.

Acedia can also manifest through an exaggerated concern for one’s physical health – specifically, Evagrius talks about the link between gluttony and acedia. The demon of gluttony convinces us that good food and plenty of it is necessary to promote good health and strength, whereas simplicity and abstinence will harm us. The Desert Fathers saw gluttony as ultimately dulling the mind which hinders contemplation.

- Aversion to [manual] work.

The Desert Fathers – like the monks of today – saw manual work as a necessary part of their life. This work was often physically hard and repetitive, but the point of it was to leave the mind free to focus its energies on God. Acedia understood as laziness towards work stems from this manifestation, but more from the later developments of John Cassian.

Evagrius, on the other hand, also saw the other danger of acedia in the form of activism or business, especially for good things. This is a kind of ‘maximalism’ in which we do more than we ought or we do things that God has not asked us to do. The aversion here consists of fleeing from God and from oneself, increasing our burden unnecessarily, and avoiding real work of one’s life.

4. Neglect of observing the rule.

Evagrius wrote his manual for monks and nuns, but what he is basically referring to in this manifestation is the neglect of the duties of our state of life. The ‘duties of our state of life’ means the obligations implied by our commitments – priesthood, consecrated life or single life. Each state of life has its own particular duties that orient us towards holiness.

Here Evagrius is saying that it is the neglect of our particular duties and the temptation to minimalism that is a sign of acedia. For example, if the monk stops praying or the parents stop looking after their children, then they are negligent in their observance of their duties.

- General discouragement.

The final manifestation of acedia is general discouragement. This can go as far as to call one’s whole life – our faith in Christ, our vocation, our current commitments – into question and tempt us to abandon all of them.

We have sets of discouraging statistics highlighting the general discouragement of Christians. Take, for example, the statistics for lifelong commitment to marriage, priesthood or religious life. In the UK, 50% of all marriages now end in divorce, and Catholic marriages are not far behind the national average. Thousands of priests ask to be laicized (meaning they resign from active ministry) and Religious ask to be dispensed from their vows every year.

Not only are the Church’s public states of life – marriage, priesthood or consecrated life – struggling with perpetual commitment, but the call, the vocation, of being a baptised person is suffering most of all. In 2016, Dr Stephen Bullivant at the Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society based out of St Mary’s University Twickenham conducted research on the number of Catholics leaving the Church. The report found that for every 1 person joining the Church, 10 cradle Catholics left. The Church is haemorrhaging away her children and she has few grandchildren.

The reasons behind all of these statistics are complex, and behind each statistic is a unique and personal story which deserves to be heard. Bearing this in mind though, I suggest that maybe – just maybe – the problem of acedia does come into it to some degree.

Those are the five manifestations of acedia as listed by Evagrius, but the good news is that he also proposes five remedies. Let’s look at these remedies now.

Remedies:

- Tears:

In the Eastern Christian tradition the gift of tears is seen as one of the basic marks of Christian living. Repentance and forgiveness are the keys of the whole Christian mystery, and to weep is a sign of repentance, which is basically an acknowledgement of one’s need to be saved. This takes us back to the introduction, when I said that acedia is understood as a lack of concern for one’s salvation. Tears, therefore, whether literal or symbolic, are about the recognition of one’s need to be saved and taking concrete acts to cooperate with God’s grace in that mission. One prime example of this is receiving the Sacrament of Confession.

- Prayer and work:

Evagrius says we should dedicate ourselves to the “execution of all tasks with great attention and the fear of God. The monastic tradition has always given an important place to work – the traditional motto of the Benedictine Order is ora et labora which means ‘pray and work’. The alternation between prayer and work is important because of how they balance our lives. This also means getting a mind-body balance: we are both physical and spiritual beings and we must attend to both parts of ourselves.

- Antirrhêtikos – meaning “contradiction” or “talking back”. This was the actual name of the manual Evagrius wrote for his method of overcoming all the evil thoughts. What Evagrius means by this is using verses from Scripture to combat temptation. So, for each of the eight evil thoughts, he lists all the main verses of Scripture which contradict and resist these temptations.

This method is the one used by Christ during his temptation in the desert (Matthew 4:1-11). We see, for example, that the tempter came to him and said, “If you are the Son of God, tell these stones to become bread. Jesus answered, “It is written: ‘Man shall not live on bread alone, but on every word that comes from the mouth of God’.

To combat the thoughts of listlessness that take away hope, Evagrius quotes Psalm 26:13: “I believe that I will see the good things of the Lord in the land of the living” to contradict it.

- Meditation on death:

One of the ancient spiritual practises in the Church was to spend time meditating on the four last things: death, judgement, Heaven and hell. Meditating on death in particular, is one of the remedies of acedia. This refocuses on the aim of our life, which is salvation and union with God.

- Perseverance:

Finally, Evagrius recommends perseverance, which he sees as the essential remedy for acedia. Perseverance means fidelity to one’s routine, one’s life, the day-in and day-out keeping going that can feel almost impossible at times.

This month of November is dedicated to the month of the dead, to all that has gone before us, to all we have lost. It is a fitting month to be contemplating acedia.

I want to end by reminding us of two promises given us by Jesus. When we are afflicted by acedia, mourning the loss of supernatural life inside us, let us remember Jesus’ promise in the Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are those who mourn for they shall be comforted” (Matthew 5:4). And where shall we find our comfort? It shall be found in Jesus Christ, who says “I am the Resurrection and the Life” (John 11:25), These are the words we need to cling to when we are facing the temptation to acedia. We need to ask Jesus to come into those places of death and barrenness inside us and restore them to life. Raised with Him, we shall be like Him, which is the greatest victory possible for us all.

[1] Ruben Pereto Rivas. The acedia and depression as care for the burial of the dead in the classical world and its contemporary echoes. 2014. Acta Med Hist Adriat. 2014;12(2):231-46. PMID:25811685.

[2] Michael Casey. The Art of Winning Souls. Pg. 65.