Kindness and Kinship: The Blazing Inferno of God’s Love

Be friends with one another, and kind, forgiving each other as readily as God forgave you in Christ. Try to imitate God as children of his that he loves and follow Christ loving as he loved you, giving himself up in our place as a fragrant offering and a sacrifice to God. Ephesians 4:32-5:2

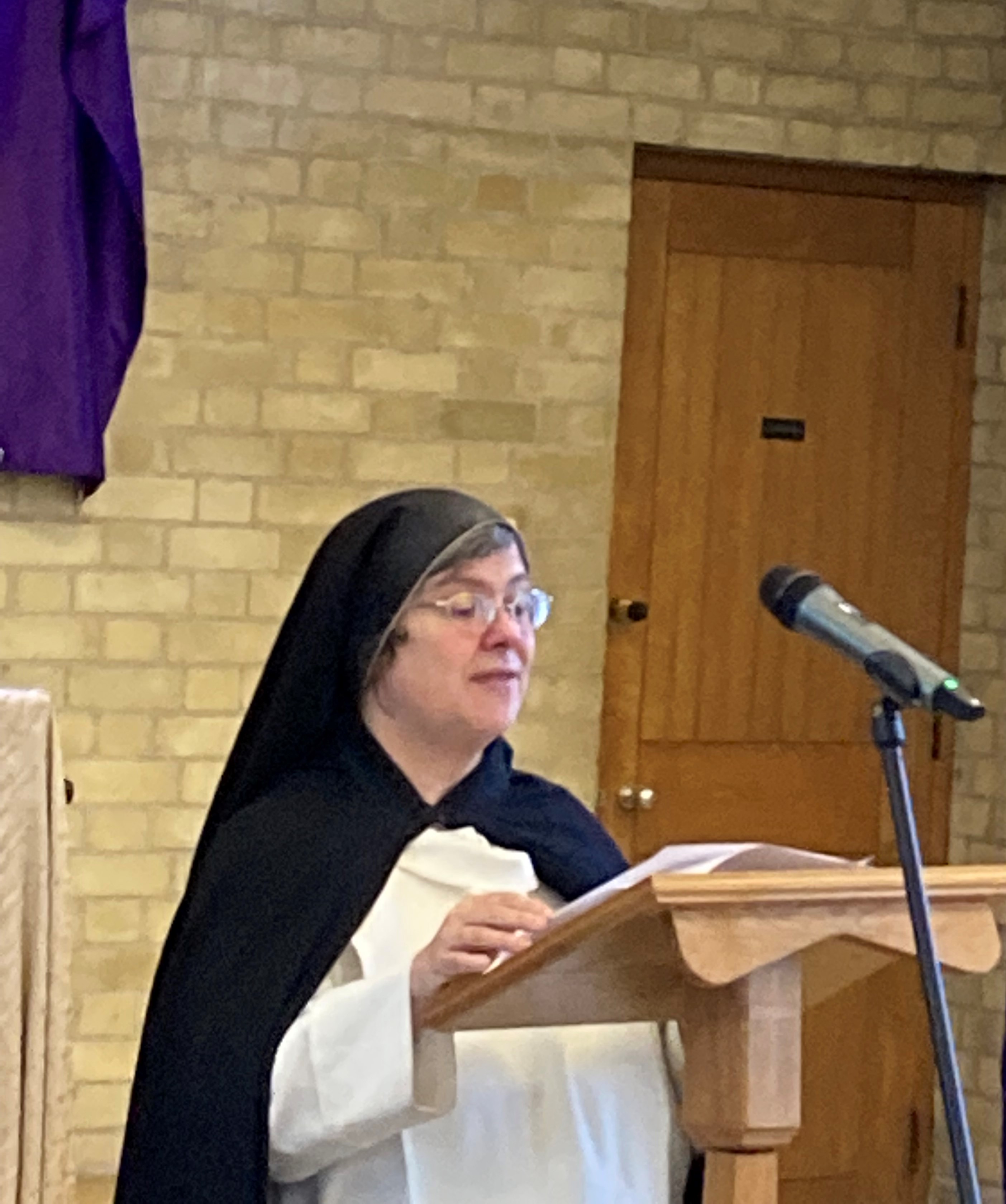

by Sr Ann Catherine Swailes o.p.

[The sisters of St. Catherine's Convent, Cambridge are giving a reflection each week at Vespers on Wednesdays in Lent. This week SrAnn Catherine reflects on kindness]

And so, here we are again in Passiontide, and as we enter this chapel, it looks different, with statues and images clothed once more in the familiar unfamiliarity of their seasonal amorphous purple. The obscuring of these obvious visual focal points at this point in the Church’s calendar, perhaps parallels for some of us at least, a kind of absence of spiritual bearings, a sense of place giving way to dis-location; perhaps tired from our efforts to do Lent well, or at a loss to know how to get back on track towards the end of a Lent that seems to have somehow passed us by this year, perhaps simply stunned by the pain of the world around us, knowing that we ought to be able to make a connection between what we consume obsessively, or turn away from queasily, in our newsfeeds, and the events we will be reflecting on in the coming days, but too overwhelmed by anger, or sorrow, or doubt, to trust ourselves to do so. In whatever state of fatigue, or anxiety, or confusion we stand at the door of the coming Holy Week, we lift the eyes of

our soul and see– well, nothing very clearly, just as the eyes of our senses have little to fix on when we gaze around us tonight.

And does the reading that the Church proposes for our meditation this evening shed any light on this encircling gloom, does it do anything to illuminate the road ahead of us, the route of the Lord’s exodus which he will accomplish in Jerusalem in just over a week from now? Well, at first sight, not so much.

The short text we have just heard read begins, after all, with a moral exhortation which sounds, at first blush at any rate, simultaneously so mundane as to verge on the trite– be kind and tender-hearted- and absolutely impossible: forgive as God as forgiven you in Christ. Be kind, be tender-hearted. Kindness, perhaps, doesn’t have quite so bad a press in some quarters as niceness, but some of us are perhaps almost as inclined to see it as negligible, evoking the idea of routine and not necessarily especially sacrificial benevolence: it doesn’t, surely, cost all that much to be kind, if we’re nicely brought up. And as for being tender-hearted – well, at least in some people’s minds, a tender heart is quite closely akin to a bleeding heart, a matter more of cheaply self-indulgent protestation of sympathy than of hard, charitable graft; an easy, sentimental tear or two before moving on. Has the Christian warfare in which we enlisted so zealously at the beginning of Lent dwindled into this? Meanwhile, can we really dare to think that the second part of this injunction of St Paul is, or ever could be, within our grasp? How can we assume, we who so routinely and perhaps vengefully, brood over petty slights, real or imagined, that we could come within light years of saying “Father forgive them” as the Lord will say these words next Friday to those who nailed him to the Cross? How is this text good news for us, rather than an invitation to mediocrity on the one hand and to despondency about our mediocrity on the other? Why is this text given to us tonight?

But are we here perhaps allowing the familiarity of these words of St Paul to blunt our imaginations to their richness, so that it is hard for us to see much connection between them and the more dramatic images of holiness that bedazzle us, the perhaps overambitious goals we set ourselves at the beginning of Lent? Now that we have nowhere else to look, it might be worth spending a little time exploring them to see if we can find in them any encouragement, any consolation, any food for our journey and light for our path in the days ahead.

Be kind and tender hearted. The word that is here translated tender-hearted is closely related in Paul’s Greek lexicon to the word used, for instance, by Jesus himself, in St Luke’s gospel to describe the compassion with which the good Samaritan responded to the man left for dead on the road to Jericho, the same word used of the Lord’s own response evoked by the leper asking him conditionally for healing – if it is your will – and this is not an affair of the heart, tender or otherwise, but of a much less romantic portion of the human anatomy: the biblical authors are speaking here of gut-wrenching fellow-feeling, emotional solidarity so intense that it reverberates in the body at, literally the most visceral level. This, then, is not simply about being inoffensively, unimpressively decent. It’s about allowing ourselves to share the messy, ugly, pain of the world in all its intensity as well as all its pathos.

At least as interesting, though, is the history of that other word that seems at first sight so slight, so bland, even, in St Paul’s exhortation: the word kind. If we think about it at all, we probably assume that the two ways in which we habitually use this word in English, as the name of a moral quality- be kind and tender-hearted – and as a way of talking about the nature of a thing – what kind of fool do you take me for? – are homonyms, words that happen to look and sound the same but have no real relationship in terms of their meaning, any more than do the bats that live in belfries and the bats with which one plays cricket. But our Medieval ancestors knew different, and better. They saw the inner, intrinsic connection here. To be kind, for our forefathers and mothers in the faith is to be true to one’s kind, to be true to one’s nature, to be the kind of creature one is meant to be. When, for instance, Julian of Norwich asked God to give her kind compassion for Jesus on the Cross, she was not merely asking to be made a bit less self-centred, a bit more warm-hearted in her concern for the suffering of another. She was acknowledging that this sympathy, this longing to comfort and console those in pain was what she was made for, and begging that God might heal her of whatever prevented her from fulfilling that vocation, which is, of course, all our vocations. And Julian’s contemporary, the poet William Langland, goes still further. For Langland, the word Kind can be used as proper noun, as one of the names of God himself, and fittingly so because God is the one who is the creator of all kinds of everything, the sheer dazzling variety of all of creation is brought forth from him, all manifesting something of his truth, his goodness and his beauty. But human beings especially are in his image. If, then, we are true to our kind in being kind, in being kind we find too that the image of God is restored in us in all its fullness. It is no milk and water respectable virtue that is at issue here, but the blazing inferno of God’s creative love. That is what it is to be kind, according to our kind, in the image of the Kind Creator who is almighty God.

And all this etymological exploration perhaps helps us too in finding a way forward with that other injunction that St Paul gives us this evening –the impossible one; the injunction to forgive as God has forgiven us in Christ. Now, you may be thinking: St Paul didn’t write his epistle to the Ephesians in Middle English. But in fact, what he goes on to say - in Greek - echoes something of what I’ve been suggesting. When we act with kindness, with the tender-heartedness that both convulses us with charity for the sufferings of others and opens our own hearts to receive the wounds that will inevitably result from such charity, then we are true to ourselves, true to our kind, and, in being true to our kind we show in our kindness our kinship - a closely related word – with the God in whose image we are made. As St Paul tells us, we are indeed to forgive as we have been forgiven by God in Christ, but this is only possible because we are, in fact, God’s children and one should expect to find a family resemblance between children and their Father. Again, in forgiving, we show our kinship with God.

God in Christ, we are told, suffered for us, leaving us an example. That quotation, of course, is not from our reading tonight, not from the letter to the Ephesians, not from St Paul at all, but from the first letter of St Peter, where the full implications of taking Christ and his sufferings as our example are spelled out. Fidelity to that example includes, centrally, the forgiveness with which Christ met his death: when he was reviled he did not revile in return, when he suffered, he did not threaten: as we know, on the contrary, he asked his Father to forgive those who knew not what they did. At first sight this seems at best like cold comfort at best, and at worst taunting us with a sense of the absolutely unachievable nature of what has been set before us for our emulation. If that is what it is to be a child of God, what is demanded of the children of God, what hope is there for us?

But what if we saw this example of Christ not so much as a pattern of behaviour to be copied as a life to be entered into? Some scriptural scholars tell us that the first letter of Peter is in fact an ancient homily for Easter Eve, preached, therefore, to those about to be baptized. It is a reminder, then, that our identity as children of God, not merely created by God, but recreated in Christ, is not a status to be achieved, but a gift to be received in our sacramental initiation into the death and rising of the Lord. We are indeed children of God, but not by our own efforts or through our own merits. We are children of God because he offered himself for us as a fragrant sacrifice, and, in that sacrifice, lies all our hope of forgiving as we are forgiven, and all the strength we need to minister tender-hearted kindness to a world in need. That truth, mysterious as it is, should be enough to guide and light us through the days ahead.