Hail the day that Sees Him rise

by Sr Ann Catherine Swailes o.p.

Whichever way you look at it, the Ascension, which we commemorated liturgically last week, seems like an odd sort of a feast, but I wonder if it’s not one that we should regard with new eyes, new expectation.

At first sight, it seems to commemorate a leave-taking; the departure of the Lord from the community which had so recently welcomed him back into their midst after his Passion and death. Psychological common sense would suggest, surely, that confusion and trauma, rather than rejoicing, would have been the disciples’ reaction, and there doesn’t seem much to celebrate in that.

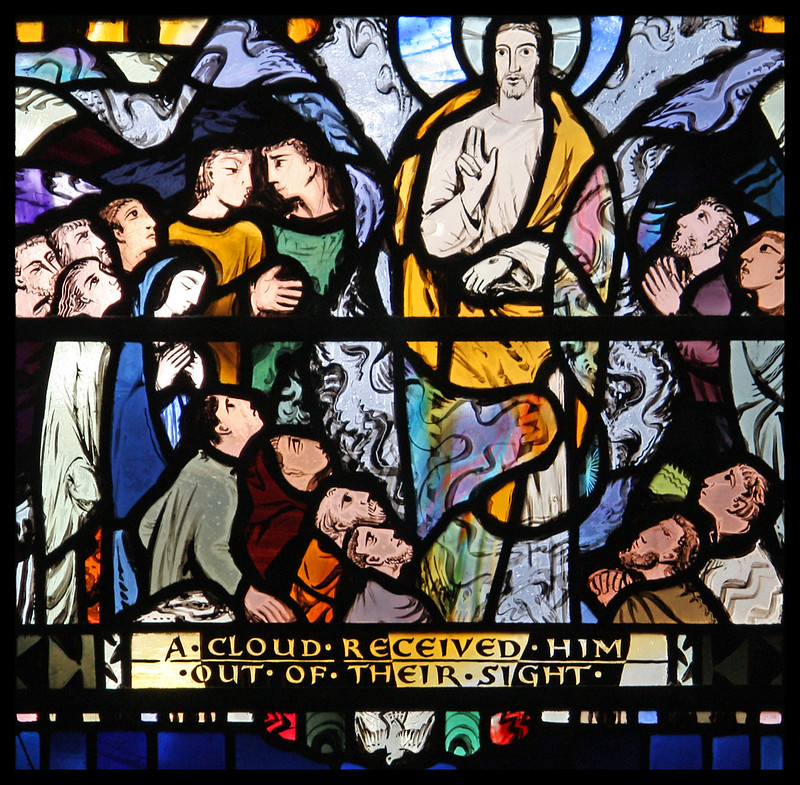

At least as strangely, according to St Luke’s account in the Acts of the Apostles, the disciples are called to account for what seems to be a

perfectly normal response to a decidedly abnormal state of affairs: they are asked why they are standing gazing into heaven after the disappearing Lord. But why ever shouldn’t they? What else would we expect them to do?

Perhaps the key to understanding all this is to realise that this feast is intended, not to emphasise our increasing distance from Jesus, as he ascends “far above yon azure height” as the old hymn puts it, but, rather, to remind us of his abiding closeness to us. It is a feast not of desolation and absence, but of consolation and presence.

If we are members of his body, even after his ascension Christ is inseparably united to us, closer to us than we are to ourselves, present with us not only in all our joys and festivity but also in all our sorrows and anxiety. As St Augustine puts it:

“Christ is now exalted above the heavens, but he still suffers on earth all the pain that we, the members of his body have to bear”.

This unity between us and Christ gives us confidence for the future: if Jesus really is the head of his body, the Church, his entrance into heaven surely gives us grounds to hope that this will one day be our destiny too.

And, paradoxically, that helps, perhaps, to make sense of that odd injunction to the disciples not to stand around staring into the bright blue yonder. Christ will return one day in glory, as we proclaim Sunday by Sunday in the Creed , and then indeed he will take his friends to be with him where he is. But, in the meantime, there is work to be done, in the strength of his Spirit and for his sake; the work of being his body, his presence, in the world he loved and came to save.

And there’s one other thing. On the feast of the Ascension, the choir of St John’s College stand, as they have for over a hundred years on this day, on the roof of their chapel tower to sing a farewell to the Lord on his journey home to heaven. The Oxonian in me has always been tempted to see in this somewhat niche Cambridge custom a pale (blue) imitation of another rather more famous occasion of tower-top music-making. On Thursday, there was no jumping in the river, no morris dancing, no bleary eyed revellers making their way home through crowded streets. Most people in the city and the university were utterly oblivious of the whole thing, which, love it or loathe it, no one could say of May Morning in Oxford. A choir simply sing a motet, those assembled in the seclusion of the court to listen,then pray and join in with a hymn. The whole thing lasts ten minutes and then everyone goes about their business. But the very hiddenness and tranquillity, even the matter-of-fact briskness of the celebration tells us something important about this feast, too. Whilst the Ascension is rightly celebrated as an extraordinary event in liturgy, and music and art, the scriptural descriptions of the episode are actually surprisingly quiet accounts. A cloud took him from their sight, we read; he withdrew from their view. There is nothing here about trumpet fanfares tearing open the sky, no blaze of glory, nothing dramatic here at all: the Lord just – leaves. And, we are told, he will return in the way we have seen him go. Perhaps one of the subtler messages of the Ascension, then, is a reminder to be on the alert for the presence of Christ in still reflection as much as in emotional noise, in the day to day and the routine, as much as in the extraordinary and the spectacular. And we shouldn’t feel despondent at his departure, or alarmed by the idea of his return, because the Lord who has risen above the heavens is with us always, in all the times and seasons of our lives, until the end of the ages.