The Sacred Heart of Jesus in the Year of Mercy

by Sr Ann Catherine Swailes

If you were producing a film, and wanted to convey that the central characters were Catholic, one of the easiest ways of doing so would be to show a shot of a picture on the wall of the family home, depicting a long-haired, bearded man in a red cloak, with a stylised heart visible on his white tunic; a heart which, on closer examination, would most likely prove to be surrounded with flames and adorned with a crown of thorns. The imagery of the Sacred Heart, in other words is easily recognisable as a “Catholic thing”, along with rosary beads, for instance, or crucifixes.

It can be treated as a kind of logo; visual shorthand for Catholic commitment; the religious equivalent of a football team strip or a membership badge. And, like football strips and membership insignia, the imagery of the Sacred Heart calls forth powerful, even visceral responses. A Methodist minister whom I met recently at an ecumenical gathering was telling me of an awkward pastoral dilemma she’d been facing: a friend who was an artist had offered to paint a picture of Jesus for her church hall, and when it arrived, it turned out to be a portrait which observed all the iconographic conventions of the Sacred Heart. The minister herself had no problem with it – she was, after all, an ecumenist, , but she knew that it might well make some of her people feel very uncomfortable, as though they were being asked to subscribe to something foreign to their own spiritual tradition. I’m not sure how she resolved the difficulty. More positively, I can remember when I was exploring the question of being received into the Church, visiting the homes of Catholic friends, and seeing there that tell-tale, and if truth be told not necessarily artistically very sophisticated print on the wall. It did indeed seem to say “this is the real thing, you actually are encountering Catholicism as a lived reality in the lives of these people”, and that was simultaneously wonderfully reassuring and terribly exciting.

But what is behind the imagery? What really is devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus? And why is it a particularly appropriate thing to be thinking about during the year of mercy?

In 1956, Pope Pius XII wrote a rather beautiful encyclical to mark the centenary of the establishment of the feast of the Sacred Heart as a universal celebration in the Church. That fact suggests that this is a comparatively modern devotion, but, as the encyclical spells out, that is very much a half truth at best. Devotion to the Sacred Heart did not begin in 1956, 1856, or even, as is often suggested, in 17th century France, though, as we’ll see, that was an important point in its development.

Like most papal documents, the encyclical is known by its opening words in Latin, in this case Haurietis aquas, you will draw water, an allusion to the psalm verse “with joy you will draw water from the wells of salvation”, which we now sing every year at the Easter Vigil And that title, in fact, makes the point immediately, which Pius XII goes on to spell out at considerable length: the essence of reflection on the Sacred Heart of Jesus, though it received the form we’re familiar with in modern times, the form which can be used, as I’ve suggested, as a symbol of Catholicism itself, is in fact as old as Christianity, and founded in the Paschal Mystery, in the death and resurrection of Jesus.

In HA, Pius XII roots devotion to the Sacred Heart in both scripture and in the great doctrines of the faith, but he does having first acknowledged that for some at least of his readers, this will come as something of a challenge. He’s aware – and over half a century later it's possibly even more obvious, that it is not only non-Catholics who find the concept of the Sacred Heart alien. With the best of intentions, the Pope points out, though, he suggests, mistakenly, some Catholics consider devotion to the Sacred Heart to be too sentimental (and certainly some of the artwork connected with it, both in terms of iconongraphy and of hymnody might well lead to that conclusion); too obsessively focussed on personal sin to the exclusion, perhaps, of concern for social justice and so on. But, Pius XII suggests, such objections either mistake distortions of the devotion for the authentic version, or at best concentrate on what is peripheral at the expense of the essential.

And if we ask what is the essential thing here, it turns out to be something in one sense very simple, so simple, in fact, that it can be embarrassing to speak about, though the Pope shows no hesitation whatsoever: the essential thing is simply the love of Christ.

I said that Pius XII roots the devotion in both doctrine and scripture, and I do urge you to read for yourself how he does this, because I think it’s very beautiful indeed. Fundamentally, the particular doctrine on which the devotion is based is what is called the Hypostatic Union, the profoundly mysterious teaching that, in Jesus, there is nothing lacking that is to be found in every human being; he has a mind like ours, a will like ours, a soul like ours, and yes, a body like ours, and that yet this humanity is united to the Word of God, the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, in a way that neither overwhelms the humanity nor dilutes the divinity: as Pius quotes from the acts of the 5th century Council of Chalcedon, Christ is “perfect in his Godhead, likewise perfect in his humanity”.

One of the things that this means is that whereas it would be idolatry to worship any other human body, in the case of Jesus we not only can but should do so, because this body belongs to God who is supremely worthy of our worship. By extension, we can talk about adoring any particular part of Christ’s body, and, in fact, over the years devotions have grown up in various places to, for instance, the face of Jesus (St Therese of Lisieux’s religious title in full was Sr Marie-Therese of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face)If we ask why in particular we should adore his heart, it is because, quite simply, of the natural symbolism of the heart: when we think of the heart we think of raised emotion in general (“my heart missed a beat”) perhaps, maybe of qualities such as courage, which, in fact is etymologically connected with the word for heart in the Romance languages cor/coeur/corizon etc (he had the heart of a lion) maybe of the self as self, (she threw herself whole-heartedly into the project) but, surely, above all, when we think of the heart, we think of love. We talk about sweethearts, about giving our hearts to those we love, perhaps most significantly about our hearts being broken when costly love is not returned. It makes perfect sense to use the divine heart of Christ as a symbol, then, of his divine love for us.

But – and this is vitally important – the doctrine of the hypostatic union can be seen from the human side as well as the divine. If we can worship the heart of Christ because it is the heart of God, this heart that we worship is also a human heart, a perfect human heart. In some very beautiful sections of the Encyclical, Pius XII uses this idea to point out the difference between the Old and the New Testament in terms of their respective ideas of the love of God. It’s worth spending a moment or two on this. As the Pope points out, it’s not that there’s nothing about the love of God in the OT. The prophetic books, and the psalms, and, of course, the Song of Songs, are full of descriptions of how God relates to his people, drawn from both parental and spousal love, and indeed the OT law suggests that this relationship is to be reciprocally one of love: “hear O Israel, the Lord our God is one Lord. Thou shalt – not serve, or fear, or obey, but love the Lord thy God with all thy heart (interestingly), soul and strength. The OT God is not only supremely loving but also supremely lovable.

The love of God does not “become a thing” when Jesus is born, then. God simply is love, and there is, of course, no time in God, and no alteration. But there is nevertheless something radically new about the New Testament. Whereas the authors of the OT use the language of human love to describe the love of God, because it’s the best, in fact the only, language we have to do that with, in the case of Jesus, his love actually IS human as well as divine. This means that when we talk of the love of Christ, we mean everything we mean when we speak of any human love, though this is a human love utterly free from sin and self-seeking. In particular, when we speak of the love of Christ, we don’t mean something dispassionate, disembodied, remotely benevolent. It is perfect human love, emotionally engaged, passionate in the best sense, it is the perfect human love with which we humans have all longed to be loved, which will, if we allow it, heal us of all those wounds that the inevitably imperfect experiences of human love that we all carry around with us have inflicted. We can all, and it’s a spiritual practice I like and commend, read every single word of Jesus recorded in the gospels as a word of perfect human love addressed to each one of us.

And the Sacred Heart is the symbol of all this. It’s not surprising, therefore, that in the traditional imagery, it is a heart on fire: if we think of the natural symbolism of fire, it’s complex, of course – fire burns and purifies (and it has that significance in Christian spirituality) but it also warms and energises as human love does. Interestingly, when St Thomas Aquinas asks the question why, if Christ’s death was a fulfilment of the OT sacrifices, it didn’t take the same form; why he was crucified rather than consumed by fire, he answers that fire was not lacking on Calvary; the fire that fulfils the fire of the burnt offering was the fire of charity burning in the heart of Jesus. And that’s very much the idea of the Sacred Heart. It is rooted, in other words, in the Passion of Christ in both senses of the word passion: in his suffering, and in the intensity of love that brings him to the Cross.

In fact, the Medieval period is full of implicit, embryonic devotion to the Sacred Heart. Julian of Norwich, for instance, the 14th century English hermit speaks of the Lord showing her, as she lays dangerously ill, the wound in his side, through which she is able to see "a fair and delightful place, large enough for all mankind that shall be saved to rest there" and "his blessed heart, cloven in two". And there is clearly a relationship between reflecting prayerfully on the heart of Jesus as symbol of his sacrificial human love, and, for instance, the spiritual practices associated with prayers focussing on each of the five wounds of Christ, culminating in a meditation on his wounded heart. These devotions were particularly popular in England on the eve of the Reformation, and surviving artefacts from the period (bench ends in churches etc) typically show a pierced heard surrounded by discrete hands and feet marked by a nail-wound. Such devotions were clearly meant to stir up love of Christ especially in response to the manifestation of his supreme love for us on the Cross. More than that, though, at least in some cases, the art work associated with the devotion to the Five Wounds shows an explicit awareness of another point which is also central to the theology of the Sacred Heart. There is a surviving banner of the Five Wounds, for instance, which was carried by the Catholics of Devon and Cornwall who mounted an uprising in 1549 against the forced imposition of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. In this depiction, the hands and feet surround a heart, but the heart is at the centre of a Eucharistic host, hovering about a chalice. The love of Christ for humanity, symbolised by his heart, not only lead him to the Cross but remains available to us in the sacraments. This, of course, is an ancient interpretation of St John’s account of what happens when Christ’s side is pierced on the cross by the centurion: out from his heart flow water and blood, traditionally taken as representing baptism and the Eucharist respectively. It is no accident that the feast of the Sacred Heart is the day after the octave of the traditional date of Corpus Christi: devotion to the Eucharist and devotion to the Sacred Heart, to the love that gives us the Eucharist, go hand in hand.

In addition, many of the greatest Medieval mystics show an awareness of the heart of Christ as symbolic of his love and of the very essence of his personality. St Catherine of Siena, for instance, has a mystical vision in which she exchanges hearts with Christ, so that henceforth she can love with his love. (Interestingly, contemporary secular literature, such as Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde, also has human lovers mysteriously exchanging hearts in an experience that is simultaneously ecstatic and painful) It is after this exchange of hearts with Christ that Catherine, who has formerly been living a very withdrawn life of intense prayer is sent out into the world to minister the mercy of Christ to the sick and the imprisoned and the ignorant. Again, there is something here which is perhaps recognisable as the forerunner of another important aspect of later devotion to the Sacred Heart, an aspect, in fact which it is probably particularly important to stress in view of the objections which are sometimes levelled against it, that it is too sentimental and saccharine, encouraging a subjective, inward-looking piety. In fact, there’s a strong moral dimension to devotion to the Sacred Heart: perhaps some of us are familiar with the traditional aspiration at the end of the litany of the Sacred Heart: Jesus, meek and humble of heart; make my heart like unto thy heart. It’s not that we’re supposed to wallow self-indulgently in nice feelings, then; rather, we’re supposed to imitate the love of Christ symbolised by his heart in active charity to our brothers and sisters. And yet, this isn’t some kind of impossible moral rigorism: we are only able to show Christ-like love because Christ, out of love for us, himself gives us the strength to do so, makes our hearts like unto his, puts a new heart into us, we might say, as St Catherine experienced him literally doing, in her vision.

There is also a stream of spiritual writing in which the mystic has the experience of interacting, as it were, with the actual, physical heart of Christ. St Gertrude of Helfta , for instance, a 13th century German abbess had a series of visions in which Christ met with her and treated her with great tenderness. In one of them, she is encouraged to rest her head against his breast and hear and feel the beating of his heart. St John the Evangelist is also present, and Gertrude asks him why, since he had also had this extraordinary privilege at the last supper, he’d not written more about the experience in his gospel. St John replies that he did not do so because it was for “a later time”. It’s important to see that this doesn’t mean that either Gertrude, or any subsequent visionary, has been given any new doctrine: Catholics are required to believe that there is no new revelation after the close of the apostolic age. But the implications of that revelation are being constantly unfolded, in ways that are particularly appropriate for the life of the Church at the time. I think it’s also worth noting that the visionary experience of Gertrude sounds rather like what might happen to anyone who contemplates imaginatively on the Last Supper. And that too may be significant when we consider that the Jesuits have been especially involved in the more recent history of devotion to the Sacred Heart.

The name probably associated above all with the devotion in the form we are familiar with, if we are familiar with it, is that of the 17th century French Visitation nun St Margaret Mary Alacoque. St Margaret Mary was born into a middle class family in Burgundy, and after a difficult childhood (her father died when she was c 8, and she endured periods of severe ill-health) she entered the Visitation monastery in Paray-le-Monial as a young woman. She did not find religious life easy: she was clumsy and slow at the domestic work she was put to in the convent infirmary, and was treated in a way that amounted to bullying by at least some of the other nuns. However, she maintained her intense childhood devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, and received sympathetic and gentle spiritual direction from St Claude de la Colombiere, the sisters’ Jesuit confessor. Over a period of 12 years, Margaret Mary had a series of visions of Christ: interestingly, the first, during the retreat just prior to her Profession, the Lord said to her “behold the wound in my side, wherein you are to make your abode, now and forever”, but the first that explicitly mentioned the heart of Christ took place on the feast of St John the Evangelist some years later. Highly significantly, she was praying before the Blessed Sacrament exposed when this happened. On this occasion, the Lord asked her to take St John’s place, leaning against his breast at the last supper. After expressing his tender love for her, he revealed his heart to her saying “my divine heart is so inflamed with love for mankind that it can no longer contain within itself the flames of its burning charity and must spread them abroad through you”. Margaret Mary saw the heart circled by flames and crowned with thorns; the Lord told her that these represented respectively his love, and human ingratitude. . In subsequent visions, he required her to promote hour-long sessions of adoration of the Blessed Sacrament – the custom we know as the Holy Hour – and to work to have a feast “of reparation” to the Sacred Heart instituted on the day following the octave day of Corpus Christi.

That word, reparation, needs a little careful handling, and thinking about this can help us, I think, to understand still more about the inner meaning of devotion ot the Sacred Heart. "Reparation" can sound as though God is demanding the impossible of us; that we put right, repair, our broken relationship with him. But the good news of the gospel is, of course, that this is not only impossible - which might, taken on its own sound in fact like rather bad news; it’s also unnecessary: God, in Christ, has already put right what we could not; has already restored us to his friendship out of sheer, unmerited love for us. But, although this is a beautiful, consoling truth, it is one that many people find hard to believe: it seems, in fact, too good to be true. Many people, moreover, in our society would, I suspect, be surprised to know that this is what the Church teaches. I think there's a general impression in our current culture that Christianity is, more than anything, about trying to enforce adherence to a rigorous and probably outdated moral code. The concept - on which Pope Francis encouraged us to reflect in his first encyclical - of the joy of the gospel, the joy of the Christian message might, I suspect, strike all too many people as something of a contradiction in terms.

If this is so for our secular contemporaries, it was also very much so in the France of Margaret Mary Alacoque's day, even amongst unimpeachably "good Catholics". And it was for that reason whilst the devotion to the Sacred Heart that Margaret Mary promoted was for some profoundly consoling, for others it was acutely controversial. The Church in 17th century France was deeply affected by a theological movement called Jansenism, after its founder, the Belgian bishop Cornelius Jansen. Jansenism has sometimes been called "Catholic Calvinism", and it certainly shares with that form of Protestantism a belief that, in consequence of the disobedience of Adam and Eve, human nature is now totally corrupt and incapable of good, whereas the Catholic understanding is that the image of God is wounded as a result of original sin but not completely effaced. Like Calvin, too, Jansen and his followers taught the doctrines of so-called limited atonement and double predestination, the idea that God, essentially, created some people in order to send them to hell, and that therefore Jesus did not die to save everyone, since some were literally beyond redemption. Art historians have noted that one can tell whether Jansensism has taken hold in a particular locality by looking at paintings and carvings of the crucifixion, and noting the position of Jesus on the Cross. Jansenist depictions, typically, show the Lord's arms raised above his head, so that his whole body forms a kind of chalice shape. Positively, of course, this stresses the idea of Jesus' death as an offering to the Father, but, more negatively, it sends out a strongly exclusive message, by comparison with more orthodox representations where his arms are spread out horizontally, as though to gather the whole of humanity into his embrace.

Unsurprisingly, Jansenism led to a somewhat grim spirituality. In particular, this had consequences for the sacramental life of the Church. Although, as I've suggested, their views on human nature had much in common with Calvinism, Jansen and his followers were anything but Protestant in their attitude to the Mass, for instance: they were as convinced as all Catholics should be that Jesus was really, substantially present on the altar once the priest had said the words of consecration. But, this admirably reverent attitude to the sacrament, combined with the Jansenists' understanding of the totally depraved character of human beings resulted in a highly restrictive policy with regard to Holy Communion. A very influential book called, "on frequent communion" by Antoine Arnaud, one of the first generation of Cornelius Jansen's disciples in France, spells this out. "Since the Eucharist is the same food that is eaten in heaven, so the purity of the faithful who receive it on earth must necessarily be that of the blessed in heaven" he says and goes on to list those who should be barred from receiving Holy Communion, including, he claims "those who are not yet perfectly united to God alone, or, to use the word of Scripture, who are not yet entirely perfect, and perfectly irreproachable". On that basis, one might be forgiven for wondering if anyone would dare to approach the sacrament, and, indeed, there are horror stories from 17th century France of pious people refusing Holy Communion on their death beds because they believed themselves to be insufficiently detached from their sins; priests who rarely said Mass not because they were lax or lazy but because they were so much in awe of the Eucharist and so much aware of their own unworthiness of it, and, as a knock-on effect of this, good and faithful Catholics who had not made their first holy communion at the age of 30 because in areas where Jansenism held sway, the Mass was so rarely available.

Against this backdrop, perhaps the idea of making "reparation" which Margaret Mary was tasked to encourage is thrown into relief a little more clearly. It's not a matter, in the first place, of our doing anything for God but of our recognising what God has done for us and being grateful for it: remember that when Margaret Mary was shown the heart of Jesus encircled by the crown of thorns and fire, they were said to represent respectively human ingratitude and the love of God that overcomes it. Of course, meditating on all this leads, rightly, to penitence: when we consider how much God has loved us, inevitably our failures to love him are all the more starkly apparent. But it also leads to the freedom from fear that makes true penitence possible: God is not an angry taskmaster who might grudgingly allow himself to be appeased by our grovelling, but on fire with love for us, and waiting for us to return to him in love - as, indeed, we heard in the gospel at Mass this morning. Reparation is above all our acknowledgement of all this: first of all, that we are not "beyond redemption", though we are incapable of saving ourselves, and secondly that God has saved us, has set us free to serve him, and has done so because of his infinite love for us, a love which he continues to make available to us in the sacraments of his Church, through which, if we let him, he will craft our hearts into models of his.

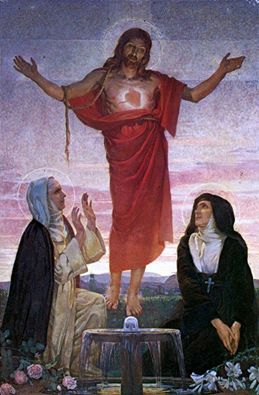

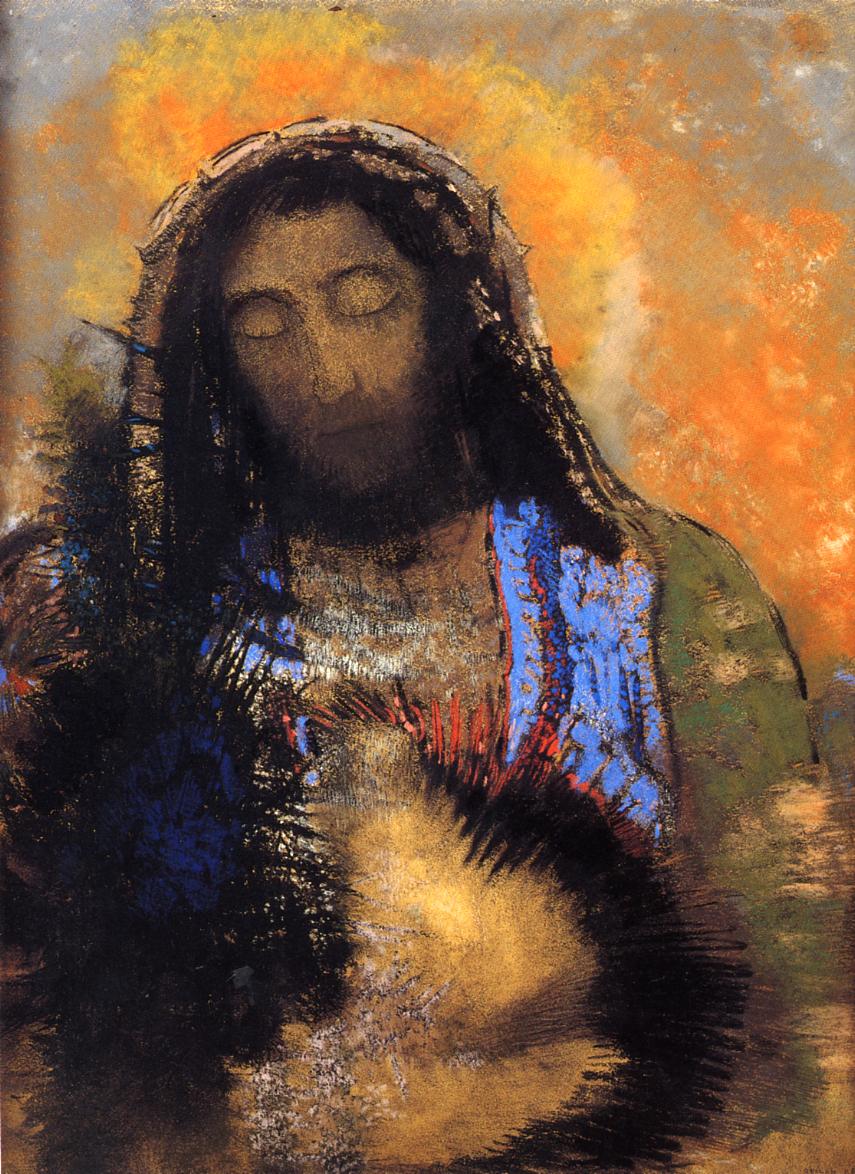

Jansenism sadly didn't simply wither on the vine, but devotion to the Sacred Heart as encouraged by Margaret Mary gave the Church in the centuries that followed, especially in France, an immense treasury of resources with which to combat it. And it's notable that much of the art connected with the Sacred Heart produced in France in the 19th and early 20th century in particular, emphasises the very themes we have just been considering : the ardour of God's love for us, our response of gratitude, and the intimate connection between devotion to the Sacred Heart and a love for the Eucharist which, whilst always reverent is also, above all confident and grateful. Here, for instance, are two rather different pictorial representations of the Sacred Heart, both of which are a bit eccentric when compared with the depictions with which we're perhaps more familiar, but which perhaps pick up key aspects of the devotion in ways which might strike us afresh.

The first is the great mosaic above the high altar in the basilica of Sacre Coeur de Montmartre in Paris. It is interesting, first of all, that, although Jesus is shown here in majesty, in a way reminiscent of both the resurrection and the transfiguration, and there is no blood visible, his arms are extended in a cruciform position - and it is very definitely not a Jansenist crucifix that is being evoked. His embrace could hardly be wider. But also, of course, below the mosaic we see a monstrance. The basilica of Sacré Coeur was built precisely for perpetual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, which has continued there day and night since 1885, uninterrupted by two world wars. Not only a vivid symbol of the love of Christ, then, but the very presence of that love at the heart of the city. If you haven't been - go!

The second is a painting by the late 19th century lithographer and painter Odilon Redon, now on display at the Musee d'Orsay in Paris. Whatever we make of the picture - and this reproduction certainly doesn't do it justice, it seems at least to me to emphasise the passionate humanity of Christ's love in a way that more conventional depictions of the Sacred Heart often fail to do. It is impossible to look at this image of Christ, I think, with anything other than gratitude and pity.

And what is true of artistic representations of the Sacred Heart is also to be found in the work of French spiritual writers of the same period. There is, for instance - and this might be a good place to stop - a wonderful prayer by St Therese of Lisieux, in which she speaks of wanting to make reparation for her sins not by acts of penance, not by pulling her spiritual socks up and trying harder, but by "casting her sins into the furnace of [Christ's] merciful love". This is precisely the point of devotion to the Sacred Heart, and it is precisely why, as this year of mercy draws towards its close, it's good to remember it.