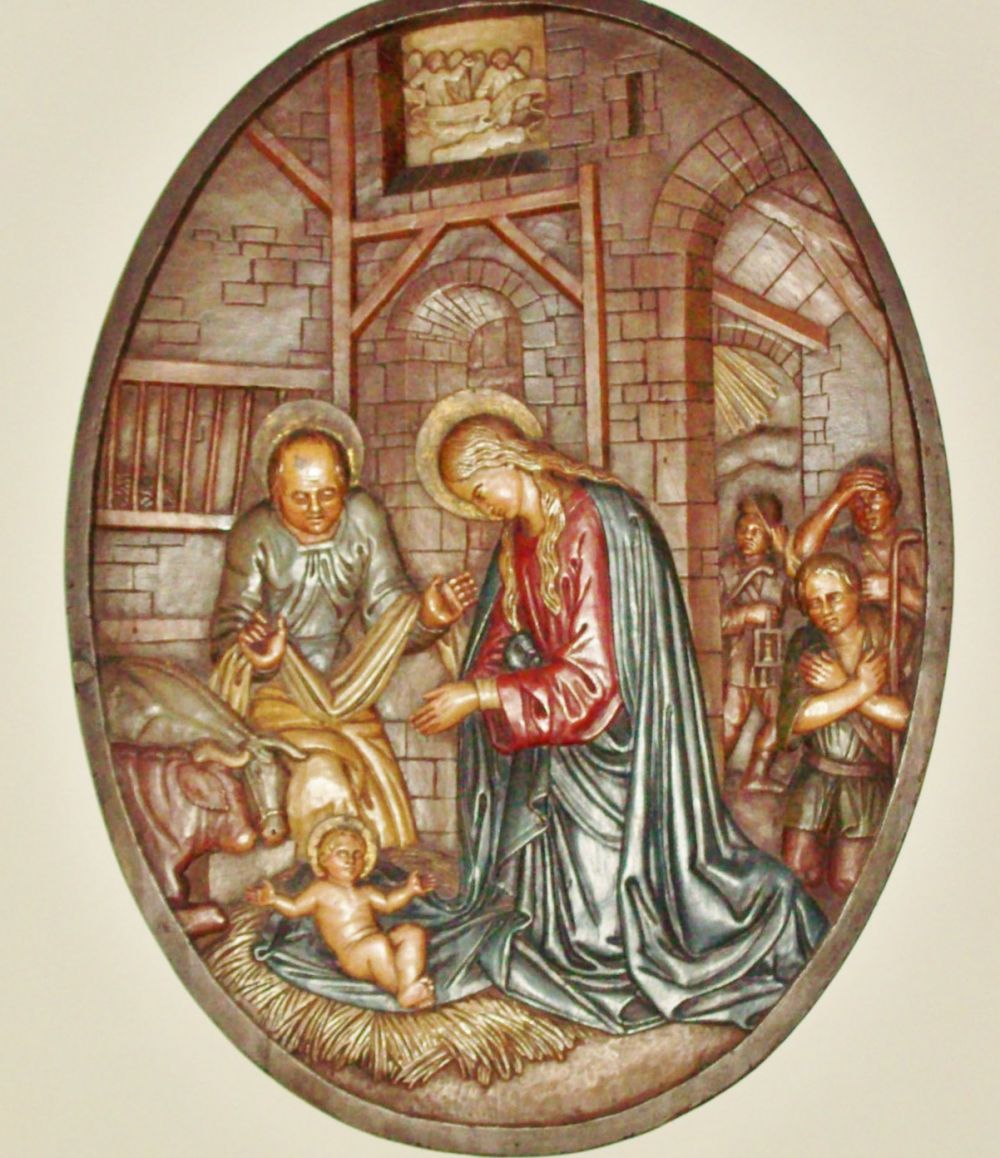

The Nativity

By Sr. Mary Magdalene Eitenmiller, OP

As John says so simply and profoundly, “No one has ever seen God; the only-begotten Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, He has revealed Him.”

This mystery began quietly in Mary’s womb, when she said her Fiat at the Annunciation. But as Christmas approaches, we celebrate the birth of the Saviour of the world — not in a palace, but in poverty. Our Holy Father, Pope Leo XIV, recently reflected on this in his exhortation Dilexi te. He reminds us that God chose to share our human fragility completely:

“We came to know Him in the smallness of a child laid in a manger and in the extreme humiliation of the cross.” [1]

Already, then, the manger points toward the cross. From the very beginning, Jesus embraces poverty, humility, and rejection. As St. Luke tells us with such poignancy,

“There was no place for them in the inn.” [Lk 2:7]

The Church has always treasured another part of this mystery as well: Mary’s perpetual virginity. She was a virgin before the birth of Jesus, during His birth, and after His birth. St. Thomas Aquinas explains that this was fitting, because the one being born was no ordinary child, but the eternal Word of God. As he beautifully puts it, just as our own spoken word does not harm the mind that forms it, so the divine Word, when born of Mary, did not destroy her virginity, but revealed God’s holiness and power. [paraphrase of ST III, q. 28, a. 2, resp.]

For this reason, the Church has always believed that Christ’s birth was miraculous and filled with joy, not suffering. Isaiah’s words are often applied here:

“Like the lily, it shall bud forth and blossom, and shall rejoice with joy and praise.” [Is 35:1-2]

This is not simply an ancient belief, but the living faith of the Church today. The Catechism tells us that Christ’s birth “did not diminish His mother’s virginal integrity but sanctified it,” [CCC 499] which is why the Church continues to honour Mary as the Ever-Virgin.

The Church’s teaching on Mary’s perpetual virginity is not an isolated or arbitrary doctrine. As with every authentic teaching about Mary, its deepest purpose is to protect the truth about Who Christ is. This is why the Catechism, when it speaks of Mary’s virginity even in giving birth, refers us back to the early Church and to the great Christological debates of the fifth and sixth centuries.

One of the most important witnesses here is Pope Leo the Great. In a famous letter written in AD 449 — later known as the Tome of Leo and solemnly received by the Council of Chalcedon — he insists that Christ is fully God and fully man, united in one person. Speaking of Christ’s birth, Leo writes that the Virgin Mary “gave birth to Him in such a way that her virginity was undiminished, just as she had conceived Him with her virginity undiminished.” [Pope Leo the Great to Bishop Flavian of Constantinople (June 13, 449), named Lectis dilectionis tuae, better known as the Tome of Leo, which was read allowed and cited by the famous ecumenical Council of Chalcedon (451) (cited in Denzinger #291). ]

Later in the same letter, he adds something equally important:

“Nor does the Lord Jesus Christ, born from the womb of a virgin, have a nature different from ours just because His birth was miraculous.” (Dz #294).

In other words, the miracle of Christ’s birth does not lessen His humanity. On the contrary, it confirms both truths at once: that He is truly human and truly divine.

A century later, Pope Pelagius I echoed this same faith, teaching that Christ “was born preserving the integrity of the Mother’s virginity; since she bore Him while remaining a Virgin just as she conceived Him as a Virgin.” [Pope Pelagius I (not to be confused with the heretic, Pelagius), wrote a letter, Humani generis (not to be confused with the encyclical with the same name promulgated by Pope Pius XII in 1950) in 557, [Dz 442.]

What we see here is a consistent witness across centuries: Mary’s virginity at Christ’s birth serves to reveal that Jesus is not a mere man touched by God, but God himself who truly became man. The Second Vatican Council expresses this beautifully in Lumen Gentium, reminding us that Mary’s union with her Son in the work of salvation is visible from the Annunciation all the way to the Cross. At His birth, the Council says, Christ “did not diminish His mother’s virginal integrity but sanctified it [as she]… joyfully showed her Son to the shepherds and the Magi.” [LG n. 57]

St. Augustine captures the wonder of this mystery with poetic simplicity when he says that Mary was “a virgin in conceiving her Son, a virgin in giving birth to Him, a virgin in carrying Him, a virgin in nursing Him at her breast, always a virgin.” [CCC 510 cites Sermon 186 of St. Augustine, Serm. 186, 1: PL 38, 999].

All of this prepares us to reflect more deeply on Christ himself. Though He is one divine person, the Son of God, He has two births: one eternal, from the Father, and one in time, from the Virgin Mary. St. Thomas Aquinas explains that Christ’s eternal birth belongs to His divine nature, while His temporal birth belongs to His human nature — yet both belong to the same divine person.

For this reason, the Church has always insisted that Mary is rightly called Mother of God, Theotokos. She is not the mother of Christ’s divinity as such, but she is truly the mother of the one person Who is both God and man. To deny this title of Mother of God, as some did in the early Church, would be to divide Christ into two persons — something the Church firmly rejects. Mary is the mother of a person, not of an abstract nature, and that person is God the Son.

Calling Mary Mother of God also teaches us something important about how God chooses to work in the world. God does not save us from a distance. He enters into human life and human freedom. By entrusting himself to Mary, God shows us that He delights in working through human cooperation. Mary’s motherhood is real, personal, and tender — and yet it is also entirely ordered to Christ. She does not draw attention to herself, but always leads us to her Son.

This is why the Church never speaks of Mary apart from Christ. Everything we say about her is ultimately meant to safeguard the truth that Jesus is one person, not divided, not confused, but truly God and truly man. When we honour Mary as Mother of God, we are really professing our faith in the Incarnation: that the eternal Son truly entered our human history and took our nature from her.

If we return, then, to the birth of Christ itself, we begin to see just how much this moment reveals about God. The eternal Son does not merely pass through human history; He enters it in the most concrete and bodily way possible — by being born. He who is begotten eternally of the Father is, in time, born of a woman. The One whom the heavens cannot contain allows himself to be contained in the arms of His mother.

The Church’s insistence that Christ’s birth was miraculous is not meant to distract us from its reality, but to deepen our wonder at it. Jesus is truly born. He truly enters the world as an infant. He truly begins a human life that unfolds in time. And yet this birth is marked by divine freedom and holiness. As the Fathers loved to say, the womb that remained closed in virginity was opened in love, not by violence or pain, but by grace.

The manger itself becomes a silent teacher. Christ is born not into comfort, but into humility. He is laid where animals feed, as if already offering himself as the Bread of Life. Wrapped in swaddling clothes, He accepts dependence, vulnerability, and need. Nothing in this scene is accidental. God chooses this way of coming to us so that no one need fear approaching Him.

And Mary, at the centre of this mystery, gives birth not only physically, but spiritually. She offers the world its Savior, and then she contemplates Him. The Gospel tells us that she “kept all these things, pondering them in her heart.” To contemplate the nativity, then, is to stand at the threshold of salvation. The child in the manger is already Emmanuel, “God with us.” The silence of the night, the poverty of the setting, and the joy of heaven together proclaim a single truth: God has come to dwell among His people, and nothing will ever be the same again.

So why does this matter for us? Because Christ did not become man simply to teach us something, but to share His own life with us. As St. John tells us,

“From His fullness we have all received, grace upon grace.” [Jn 1:16-17]

Christ shares this grace with us through His humanity. Jesus is called the Head of the Church because He lives in His members by grace, making us alive to the Father as participants in His own divine life.

The Catechism reminds us that to enter the Kingdom, we must become like children — humble, receptive, and dependent. Christmas, it says, is the mystery of a “marvellous exchange,” summed up in the Church’s ancient prayer:

“Man’s Creator has become man, born of the Virgin.

We have been made sharers in the divinity of Christ

who humbled himself to share our humanity.” [CCC n. 526]

This does not mean that we cease to be human. Rather, we are healed, elevated, and drawn into friendship with the Trinity. Through grace, we are invited to share in the Son’s relationship with the Father — a relationship meant to last forever.

So as we pray, especially on retreat, we are invited to contemplate this wondrous union: Jesus Christ, true God and true man. The same God-man whom we adore as a child in Bethlehem is the one who died for us on the Cross, rose from the dead, ascended into heaven, and now comes to us at every Mass in holy Communion.

God so loved the world that He sent His only Son — not only once, in history, but continually, in grace, to every soul that receives Him. The humility of the stable reveals the glory of heaven. As the Church sings each Christmas night:

“The Virgin today brings into the world the Eternal,

and the earth offers a cave to the Inaccessible.

For you are born for us,

Little Child, God eternal.”

[CCC n. 525, citing Kontakion of Romanos the Melodist]

[1] Pope Leo XIV, Dilexi te, Apostolic Exhortation to All Christians on Love for the Poor (4 October, 2025), n. 16.